It is thought that one in every 650 people in the UK has been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, a chronic, inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract which evidences itself through pain, diarrhoea, anaemia and weight loss. It occurs most commonly in the ileum, jejunum or colon, but can also present in the oesophagus, stomach or duodenum. There is increased incidence of the disease in women, smokers, and certain ethnic groups. Patients are typically diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 40 (Crohn’s and Colitis UK, 2013), with up to a third receiving a diagnosis before the age of 21 (Gomez, 2000). Interestingly, there has previously been thought to be an increased incidence in twins proposing a genetic cause (Tysk et al., 1988). However, more recent studies have suggested that this study overestimated the influence of genetics on Crohn’s Disease (Halfvarson, 2011). Sufferers typically experience acute symptomatic attacks followed by periods of remission. Complications, such as abscesses, intestinal obstruction, fistulae, strictures and perforation, can arise and additionally, Crohn’s disease is also associated with joint, liver, skin and eye abnormalities (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2012). As a result, patients who suffer from Crohn’s disease are likely to undergo a great deal of imaging in the management of their condition. Because of the nature of the disease, images are required to demonstrate not only anatomical indicators, such as mucosal ulcers, stones, separated bowel loops and thickened folds, but also provide functional information about activity. There are a vast number of examinations which can be used to image Crohn’s disease and its complications. This post considers some of those which can be used in the evaluation of Crohn’s disease, as well as the factors and circumstances which must be taken into account when making a decision.

According to UK patient-facing information, the initial investigation of patients presenting with Crohn’s disease-like symptoms involves a physical examination, a blood test for anaemia and a stool test for signs of bleeding and inflammation (Crohn’s and Colitis UK, 2013; National Health Service, 2018). Prior to deciding the method of disease management which could be drug therapy, nutritional changes or surgery, imaging is needed to determine the location, extent and severity of the disease.

Abdomen x-rays are accessible to GPS for referral and can be used to demonstrate kidney stones, obstruction and perforation, yet they cannot provide information on the location of inflammation, thickness of the bowel wall or the disease’s effect on vasculature. There is more of a role for x-ray in in following-up complications. Because Crohn’s disease is a secondary cause of osteoporosis, the NICE guidelines recommend dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to monitor bone density in young people identified with risk factors such as low body mass index (BMI) and glucocorticosteroid use (NICE, 2012). Plain film imaging may also be required as patients get older in order to diagnose or monitor arthritis.

Traditionally for diagnosis, barium follow-through films were used but cross-sectional imaging is increasingly replacing barium fluoroscopy in small bowel imaging as it can assess location, extent, severity and complications simultaneously (Taylor et al., 2018). The use of contrast is valuable in assessing wall thickness and patterns. Yet, Ilangovan et al. (2012) suggest that using barium can conceal intraluminal haemorrhage and so should not be used unless it is needed to highlight an obstruction. However, this seems counterproductive as administration of large amounts of contrast is not advisable when querying an obstruction because in the event of a positive diagnosis, it could exacerbate the problem. Wireless capsule endoscopy is an interesting, relatively new and painless option for patients in whom a gastrointestinal bleed is queried. It involves swallowing a capsule containing a camera which images the patient’s bowel as it travels through over the course of ten hours (NICE, 2004; Cotter et al., 2014).

More invasive procedures include colonoscopy, and endoscopy which can be time-consuming , require sedation, a nursing team and a hospital bed for recovery afterwards. Thus, they are far from ideal but, for example, are still recommended by NICE guidelines to screening patients who have experienced Crohn’s disease symptoms for more than 10 years for colonic cancer (2011). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for evaluating remission in patients following surgery (NICE, 2012).

CT

CT enteroclysis involves the insertion of a nasojejunal tube for the administration of water as a neutral contrast material in addition to an injection of intravenous contrast (Gianlunca et al., 2012). Ilangovan et al. (2012) argue that, while a neutral contrast provides maximum contrast between the lumen and bowel wall, water will provoke rapid reabsorption and thus result in suboptimal distension. Good distension and contrast enhancement demonstrates abnormal bowel loops well, an indication of mesenteric fat changes, as well as highlighting any fistulae or ulceration. Despite producing optimal contrast enhancement, enteroclysis is an unpleasant procedure for the patient and entails the risk of perforation. An alternative is enterography which requires the patient to drink oral contrast over 40-60 minutes rather than be intubated, which is more tolerable to patients but requires their compliance (Ilangovan et al., 2012). This could be an issue with paediatric patients. A drawback of both these procedures is that they are time-consuming and incur a radiation dose of which the average is 15mSv (Ilangovan et al, 2012). This could be further reduced through use of automated exposure controls, tube axes modulation and adjusting the parameters and exposure factors. For an older Crohn’s disease sufferer, in whom radiation dose is not such a concern, CT is perhaps the most relatively inexpensive, informative and accessible option. It is important to consider, however, the mean sensitivity and specificity of CT in 33 studies was calculated as 84.3% and 95.1% respectively (Horsthuis et al., 2008). While still high, the sensitivity is lower than ultrasound, MRI and nuclear medicine. Consequently, depending on the accuracy required, another modality may be more suitable.

MRI

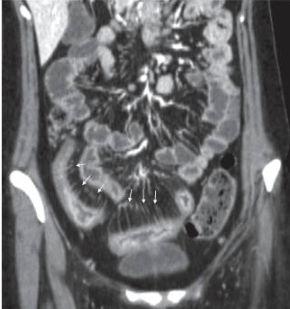

Kim and Ha (2003) describe magnetic resonance (MR) enteroclysis as the most accurate method of visualising Crohn’s disease, since it provides good distension of bowel loops. A major benefit of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the ability to produce high quality, multiplanar images with excellent soft tissue contrast without radiation exposure. Yet, as the study does not mention which type of scanner was used in the research, it may not be comparable to more modern technology. Hence it may be a little outdated, and lacks acknowledgement of more recent developments, such as 3D rendering, virtual colonoscopy, and ‘fly-through’ which can be additionally valuable in bowel assessment. However, this conclusion is supported by Gianluca et al.’s more recent review which maintains its validity (2012). Taylor et al. (2018) highlight that MRI is indeed highly accurate with a sensitivity of 97% for detecting disease presence and 80% for extent of disease. The use of a large sample size of 284 patients from 8 different UK hospitals supports the study’s reliability, generalisability and relevance to UK healthcare practice. In practice, enterography is preferred over enteroclysis, likely due to the lack of intubation needed, despite producing inferior bowel distension (Gianluca et al., 2012). Lymph node enhancement and contrast uptake by the small bowel wall demonstrates the extent of disease activity (Kim and Ha, 2003). Scanning in different sequences provides visualisation of the mesenteric vasculature which is important as activity is indicated by enlargement and engorgement of these. This produces a so-called “comb sign” which is demonstrated by Figure 1 (Ilangovan, 2012). Considering that patients with Crohn’s disease require follow-up imaging and often receive their diagnosis while young, it is important to limit radiation exposure as much as possible, therefore in addition to its high sensitivity, MRI appears an ideal option (Panes et al., 2011).

Figure 1: A CT scan demonstrating the “comb sign” From British Journal of Radiology (2012)

Pregnancy care

Stern el al. (2014) studied the effectiveness of an MR enterography protocol in pregnancy. While its international location (Israel) and use of a small sample size (n=9) may affect the generalisability of this research to the UK, it remains useful in highlighting MRE as a valuable tool in the investigation of Crohn’s in pregnant women while minimising foetal risks. Crohn’s disease carries the risks of pre-term delivery and low birth weight hence the importance of imaging, not only to check foetal growth, but also to monitor the mother’s symptoms. Computed tomography is generally a less favoured modality in pregnancy due its risk of radiation dose to the foetus. While literature demonstrates a lack of consensus over potential acoustic, heating and magnetic field effects on the foetus, MRI is considered to have no known adverse effects (Bulas and Egloff, 2013). Despite this, in the UK it is advised that a scan should be postponed until after delivery if possible, and that if a scan must go ahead, gradient echo sequences and acoustic lessening modes should be utilised to reduce any potential adverse effects. The greatest issue is the use of gadolinium-based contrast which is not recommended in pregnancy unless absolutely necessary due to concerns over potential deposits left in the body (Society of Radiographers, 2016). Mannitol was utilised in this study instead, while fast-acquisition mode can compensate for the lack of glucagon or Buscopan, minimising the effect of bowel movement on image quality (Stern et al. 2014).

While seemingly the best modality to use, in reality MRI may not be accessible to a patient due to location or the length of waiting times and it is a comparatively expensive modality. Contraindications, such as some pacemakers or metal foreign bodies, as well as claustrophobia, may also prevent it from being a realistic modality option for patients with a chronic condition. For pregnant patients, there may be image interpretation difficulties as soft tissue differentiation is lessened, in addition to anatomical changes which have taken place in the abdomen naturally due to pregnancy. Therefore, it may necessary to use a combination of MRI and ultrasound to increase accuracy.

Ultrasound

Considering its relative low cost, accessibility, lack of radiation and patient discomfort, ultrasound is a valuable modality for monitoring, especially in the care of paediatrics and pregnant women. It allows the measurement of wall thickening, demonstrates narrowing of the lumen, and confirms the presence of fistulae, perienteric fat, increased lymph nodes and abscesses, with the highest sensitivity in more accessible areas such as the ileum and left colon (Gianluca et al, 2012). There are also the added benefits of using Doppler to analyse the superior mesenteric artery flow volume as well as the interventional potential of endoscopic ultrasound to take a biopsy for histological examination. The study by Taylor et al. (2018) found that in detecting the presence of Crohn’s disease ultrasound has a good sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 84%. Therefore, it is accurate enough to be a valuable imaging tool in the initial investigation of Crohn’s disease. Because it also has sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 81% in measuring the extent of disease, it can also be used in follow-up investigations. Although MRI is clearly much more accurate in the measurement of extent (sensitivity=80%; specificity=95%), it is not as accessible or as cheap as ultrasound. However, ultrasound’s accuracy is somewhat dependent upon the operator, patient size, and the location of the disease.

Nuclear medicine

99m Tc-HMPAO-labelled Leukocyte Scintigraphy (TLLS) is theoretically an ideal technique to use since it highlights the areas of inflammation throughout the whole body, impacting on the next stage of the patient pathway. As it shows arthritis, it highlights not only the severity of the disease in the gastrointestinal tract, but also complications of it. Rispo et al. (2005) found that the sensitivity when combining this technique and ultrasound was 100%. While this study had a decent sample size of 80 patients, only 50 were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease which may affect its validity. Yet, its statistical results were comparable to the slightly more recent study by Horsthuis et al. (2008) which used a much larger sample size from 33 studies (Table 1). Gianluca et al. (2012) describe a number of advantages including the lack of risks or contraindications and good levels of toleration, however examinations are time consuming and are best for highlighting acute cases due to low anatomical resolution. Also, there is a requirement for specialist staff training which may mean that this modality is inaccessible to some patients.

Table 1: Comparison of research studies’ results of the accuracy of different modalities and examinations in the assessment of Crohn’s Disease

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Reference | About the Research | |

| Ultrasound | Conventional ultrasound | 83-87 | 95-99 | Panes et al. (2011) | Systematic review of studies into Crohn’s disease imaging. Selected 5 studies including 1029 patients for analysis- large sample size |

| 92 | 84 | Taylor et al. (2018) | A UK multicentre trial published in a reputable, peer-reviewed journal The Lancet.

Large sample size of 284 and the fact that multiple centres were used promotes its reliability, generalisability and relevance |

||

| 87.8 | 84.5 | Horsthuis et al. (2008) | Published in Radiology- endorsed by Radiological Society of North America. Large sample size using data from 33 studies. Limitations are that sensitivity and specificity values are means so accuracy is affected. Also, the research is generalised to include inflammatory bowel diseases rather than just Crohn’s disease | ||

| 92.0 | 97.0 | Rispo et al. (2005) | Published in peer-reviewed journal Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Sample size of 80 patients; 50 had Crohn’s disease, therefore the results may relate more generally to abdominal imaging rather than Crohn’s disease specifically |

||

| 90.3 | 93.7 | Migaleddu et al. (2009) | Published in reputable journal (American Gastroenterological Association). Image evaluation was by 2 blinded radiologists.

Limitations include small sample size (47 patients) however these are restricted only to patients with Crohn’s Disease |

||

| Contrast enhanced ultrasound | 93.5 | 93.7 | Migaleddu et al. (2009) | As above. | |

| Doppler | 90.3 | 93.7 | Migaleddu et al. (2009) | As above. | |

| Nuclear Medicine | 99mTc-HMPAO | 90.0 | 93.0 | Rispo et al. (2005) | As above. |

| 89.7 | 95.6 | Horsthuis et al. (2008) | As above. | ||

| MRI | Enteroclysis

|

93.0 | 92.8 | Horsthuis et al. (2008) | As Above. |

| 78.0 | 85.0 | Panes et al. (2011) | As above. | ||

| Enterography | 97.0 | 96 | Taylor et al. (2018) | As above. | |

| CT | 84.3 | 95.1 | Horsthuis et al (2008) | As above. | |

Conclusion

There is not a single ‘gold standard’ method of imaging Crohn’s disease (Gianluca et al., 2012), as patients with Crohn’s disease have a very complex healthcare pathway. Choices must reflect the chronic nature of the condition and thus minimising the radiation dose should be a priority. Procedures should be low cost, non-invasive and well-tolerated. As the majority of Crohn’s sufferers will undergo surgery at some point, they may require imaging during theatre and for complications which require them to undergo other examinations such as DEXA or CT scans. Therefore, in terms of long-term management of Crohn’s disease, ideally MRI and ultrasound should be used to keep the radiation dose of young patients to a minimum. Research has shown that both modalities can accurately confirm the presence of the disease, while MRE has the highest sensitivity in monitoring the extent and severity of the disease. Compared with optical imaging modalities, it provides high quality cross sectional analysis of bowel structure with reduced patient discomfort, as well as information about the surrounding blood vessels, which is important in forming a treatment plan. However, there are issues with accessibility, waiting times, contraindications and cost which may mean that CT is used instead. The continued development of hybrid imaging, especially PET/MRI, may be valuable in the assessment of Crohn’s Disease since it would produce highly accurate anatomical information with functional information about activity. This could be another interesting blog topic.

References:

Bulas, D and Egloff, A. (2013) Benefits and risks of MRI in pregnancy. Seminars in Perinatology [online]. 37(5), pp. 301-304. [Accessed 28 November 2018].

Cotter, J., Dias de Castro, F., Moreira, M. and Rosa, B. (2014) Tailoring Crohn’s disease treatment: The impact of small bowel capsule endoscopy. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis [online]. 8(12), pp. 1610-1615. [Accessed 28 November 2018].

Crohn’s and Colitis UK (2013) Crohn’s Disease [online]. London: Crohn’s and Colitis UK. Available from: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-inflammatory-bowel-disease/crohns-disease [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Gomez J. (2000) Living with Crohn’s Disease (Overcoming Common Problems). London: Sheldon Press.

Gianluca, G., Graziella, G., Veronica, M., Cinzia, L., Luigi, M., Ilario, S., Antonio, R. and Roberto, G. (2012) Crohn’s Disease Imaging: A Review. Gastroenterology Research and Practice [online]. No volume (no issue number), pp.1-15. [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Halfvarson (2011) Genetics in twins with Crohn’s disease: Less pronounced than previously believed? Inflammatory Bowel Diseases [online]. 17(1), pp.6-12. [Accessed 26 November 2018].

Horsthuis, K., Bipat, S., Bennink, R. and Stoker, J. (2008) Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosed with US, MR, Scintigraphy, and CT: Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. Radiology [online]. 247(1). [Accessed 28 November 2018].

Ilangovan, R., Burling, D., George, A., Gupta, A., Marshall, M. and Taylor, S. (2012) CT enterography: review of technique and practical tips. British Journal of Radiology [online]. 85(no issue number), pp. 876-886. [Accessed 24 November 2018].

Kim, K. and Ha, H. (2003) MRI for small bowel diseases. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI [online]. 24(5), pp. 387-402. [Accessed 14 November 2018].

Migaleddu, V., Scanu, A., Quaia, E., Rocca, P., Dore, M., Scanu, D., Azzali, L. and Virgilio, G. (2009) Contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic evaluation of inflammatory activity in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology [online]. 137(1), pp. 43-52. [Accessed 28 November 2018].

National Health Service (2018) Crohn’s Disease. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/crohns-disease/diagnosis [Accessed 23 November 2018].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2004) Wireless capsule endoscopy for investigation of the small bowel [online]. London: Department of Health. (IPG101). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg101 [Accessed 28 November 2018].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2011) Colorectal cancer prevention: colonoscopic surveillance in adults with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas [online]. London: Department of Health. (CG118). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg118 [Accessed 23 November 2018].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2012) Crohn’s Disease: Management in adults, children and young people[online]. London: Department of Health. (CG152). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg152 [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Panes, J., Bouzas, R., Chaparro, M., Garcia-Sanchez, V., Gisbert, J., Martinez de Guerenu, B., Mendoza, J., Paredes, J., Quiroga, S., Ripolles, T. and Rimola, J. (2011) Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn’s disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics [online]. 34(2), pp. 125-145. [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Paredes, J., Ripolles, T., Cortes, X., Reyes, M., Lopez, A., Martinez, M. and Moreno-Ossett, E. (2010) Non-invasive diagnosis and grading of postsurgical endoscopic recurrence in Crohn’s disease: Usefulness of abdominal ultrasonography and 99m Tc-hexamethylpropylene amineoxime-labelled leucocyte scintigraphy. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis [online]. 4(1), pp.537-545. [Accessed 23 November 2018].

Rispo, A., Imbriaco, M., Celentano, L., Cozzolino, A., Camera, L., Mainenti, P., Manguso, F., Sabbatini, F., D’Amico, P. and Castiglione, P. (2005) Inflammatory Bowel Diseases [online]. 11(4), pp. 376-382. [Accessed 28 November 2018].

Society of Radiographers (2016) Safety in Magnetic Resonance Imaging [online]. London: Society of Radiography. Available from: https://www.sor.org/learning/document-library/safety-magnetic-resonance-imaging-1 [Accessed 29 November 2018].

Stern, M., Kopylov, U., Ben-Horin, S., Apter, S. and Amitai, M. (2014) Magnetic resonance enterography in pregnant women with Crohn’s disease: case series and literature review. BMC Gastroenterology [online]. 14(no issue number), pp. 1-9. [Accessed 24 November 2018].

Taylor, S., Mallett, S., Bhatnagar, G., Baldwin-Cleland, R., Bloom, S., Gupta, A., Hamlin, P., Hart, A., Higginson, A, Jacobs, I., McCartney, S., Miles, A., Murray, C., Plum, A., Pollok, R., Punwani, S., Quinn, L., Rodriguez-Justo, M., Shabir, Z., Slater, A., Tolan, D., Travis, S., Windsor, A, Wylie, P., Zealley, I. and Halligan, S. (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel ultrasound for the extent and activity of newly diagnosed and relapsed Crohn’s disease (METRIC): a multicentre trial. The Lancet [online]. 3(8), pp. 548-558. [Accessed 26 November 2018].

Tysk, C., Lindberg, E., Jarnerot, G., Floderus-Myrhed, B. (1988) Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. A study of heritability and the influence of smoking. BMJ [online]. 29(7), pp. 990-996. [Accessed 26 November 2018].

Hi Rosie

Talk about ending on a high! This is an excellent piece of work. You have provided a very good discussion analysing a range of DI tests, There is also good critical evaluation of the supporting material too. It would have been worth highlighting that Crohn’s can occur anywhere in the GI tract and is a chronic disease with repeated flare-ups that require imaging each time.. Both these factors influence the choice of imaging, particularly if it’s the small bowel where endoscopy/colonoscopy is not possible (although they have now developed Wireless Capsule Endoscopy. Also, enterography/enteroclysis is usually performed pre- and post-contrast as uptake in the bowel wall confirms inflammation.

Other than that, you have a good foundation here should you choose to do it for your case study.

Overall, you have produced a very good set of blogs this term. Well done.

Simon

LikeLike